Oct. 2, 2022: one day after global protests for freedom in Iran and 16 days after Jhina/Mahsa Amini was killed by the Islamic Republic.

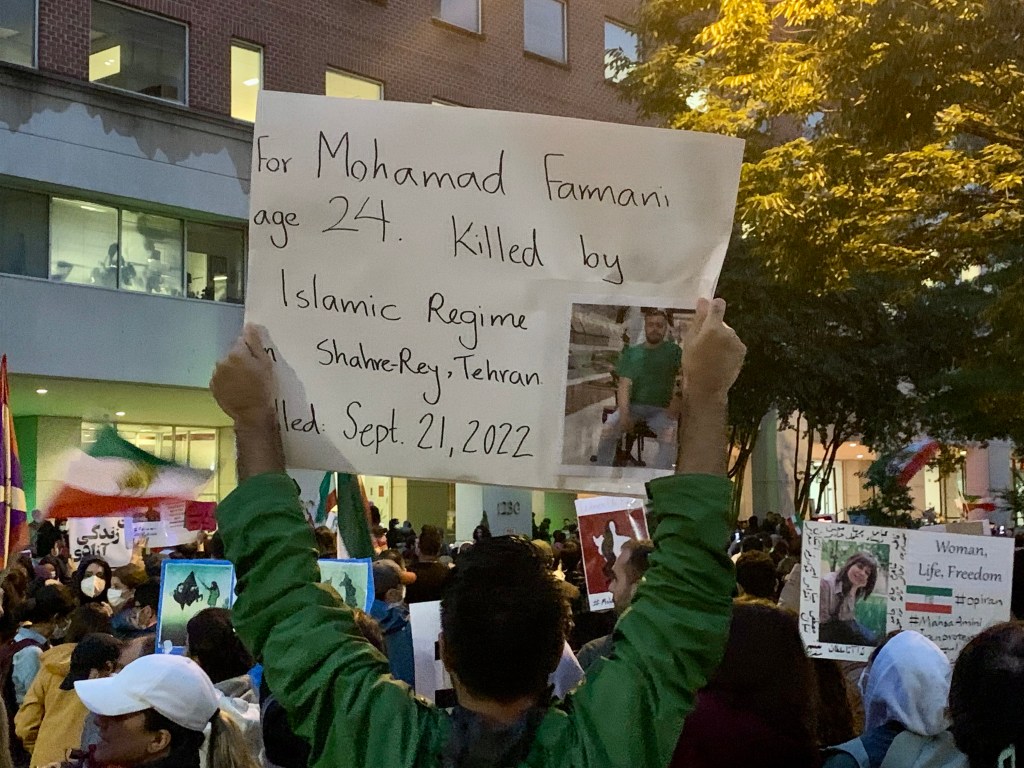

Photos taken at the Oct. 1, 2022 protest for Iran in Washington, D.C.

Will there be change?

Is this the change? Are we witnessing it right now? Are we participating in it?

Every step I take feels like a drumbeat to “Zan, Zendegi, Azadi.” I hear it as I lie in bed, tossing and turning to the rough, rhythmic chant of the woman behind the loudspeaker last night. It plays over again in my mind, her voice hoarse from days of yelling for Iran’s freedom up and down the streets of Washington, D.C. I hear echoes of “baraye daneshamoozha, baraye ayandeh,” (“for the students, for the future”) as hundreds of people around me sing Shervin Hajipour’s melody into the night. A little girl several rows behind me yells “Azadi! Azadi!” as Shervin’s voice fades into the piano in the tinny recording. Earlier in the night, I saw her marching with her mother, wearing a rainbow puffer jacket and screaming at the top of her lungs. I see the woman next to me with her face in her hands, grief pouring from her eyes. I wonder if she’s crying for a homeland lost or for the dream of homecoming. Maybe she’s crying because she knows the voice we’re listening to may be gone forever.

I didn’t know who Shervin Hajipour was forty-eight hours ago, but by last night my heart felt tight and my eyes burned as I heard the pain and beauty in his voice echoing off the buildings in Farragut Square. I had spent the whole afternoon watching the video of him singing “Baraye” over and over again, weaving together sentiments of Iranians expressing their hopes for freedom. It seems I wasn’t the only one; hundreds of us knew all the words by heart. I wonder if all of us sing loud enough around the world, whether he can hear us from his cell. I wonder if he’ll ever be able to sing it with us.

Shervin’s voice, his face, have joined countless others in my mind and heart. My head feels cluttered with all the images of pain and bravery and freedom. I don’t know how to parse them, how to understand and to respect them, how to make peace with the insurmountable gulf between where I sit now in my car in the rain outside my favorite cafe, and the streets of Iran where my people are fanning the flames of revolution. I don’t know to understand and use my freedom.

In the crowded corners of my mind where he lives, many of Shervin’s neighbors remain nameless in my imaginations of them, just as they are in the clips circulating on social media. As I wake and as I sleep, I see women with faces tilted up to the sky, dancing in circles, their outstretched arms clasping hijabs that flow as freely as their hair in the breeze; I see the blood-soaked shirts of men killed in the streets and a passerby folding his coat to place under another man’s limp head. How twisted it feels that the blood running on the streets has become the accelerant keeping alive the fire of change.

I see #zan_zendegi_azadi written in chalk on blackboards of classrooms and undersides of school desks, and children ripping page after page of Khamenei’s face from their textbooks.

I see a woman tying up her short dyed-blonde hair with palpable determination as she faces a group of police, another walking fiercely into a congregation of officers and yelling for freedom at the top of her lungs. I’ve seen rumors that both of these women are dead. I know for a certainty that over 130 other lives have been taken by the regime since Jhina’s death two weeks ago. Hadis Najafi. Hananeh Kia. Mohamad Farmani. The list goes on and on.

When the crowd screamed “betarseed, betarseed, ma hameh Mahsa hasteem,” (be afraid, be afraid, we are all Mahsa) I think this is what it meant: for all of us, individually and as a whole, to embody the strength and the spirit of Mahsa, Hadis, Hananeh, Mohamad. They cannot kill all of us. When we stand so close together and scream so loud, when our blood and our fear and our dreams get all mixed up with our neighbors’ — when we have become one another — they won’t be able to kill even one of us.

Shervin became all of us when he sang a melody to the snippets of dreams written by Iranians on Twitter — “for dancing in the street, for the yearning for a normal life, for the students and for the future, for women, life, and freedom.” He sang our dreams into an anthem and now that his voice has been confined to a prison cell, we sing it like a prayer, like a rallying cry. We became his voice so that his life could extend beyond cell walls. Just like Jhina/Mahsa’s name became a code to break free, Shervin’s song has become an invitation to dream.

We are dreaming, singing, marching the change into being.

It turns out hope is addictive. When I was small, I would dream about stepping off the plane in Shiraz for the first time, walking down a long ramp onto the tarmac and placing my Iranian feet onto Iranian land. I imagined looking up at the sky and knowing I was breathing the same air as my ancestors, walking down the streets of an almost mystical homeland I had only seen in photographs. I saw myself standing in Iran with my mother and my mother’s mother the way they did before I was born. I never dared to imagine those thoughts into words until last week, when women began setting fire to their hijabs and chanting for freedom. But now that we’re all singing our dreams together, it doesn’t seem that far away.

Standing shoulder to shoulder with Iranians and allies here and in cities around the world, I can no longer imagine living an alternative to our dreams. Going back to a world where Jhina’s death, Shervin’s imprisonment, and our collective exile all persist feels impossible. Letting their names turn from shouts to whispers to silence on our lips is unimaginable.

There is no way to calculate or describe the change that is necessary to make their dreams and ours come true. Maybe we are the change. Maybe this is just another foreshock preceding an earthquake of life-altering disruption. Whatever will be, we can never go back now that we have tasted the sweetness of our dreams.

Leave a comment